How Can a “Good” God Allow It?

Tracey, a young, healthy nurse working among the disadvantaged, is driving from one town to another when the engine of her car dies. Passersby offer to tow her car, and as that is happening, she drives over the tow rope, which flips her car over and into a ditch.

“I cannot move a muscle and feel as if the entire roof of the car is pressing down on my head,” she recalls in her book about the accident and its consequences. “Many hours later… all I can feel is the most excruciating pain in my neck…and my brain knows that I can’t feel anything below my shoulders….” Soon she feels “a stabbing pain at the back of my head.” This turns out to be caused by a sharp twig encased there.

Tracey would never walk again or regain the use of her arms or hands. She had to resign herself to being a quadriplegic for life.

Bitter Questions

Richard Leonard tells this story about his sister in his own book, saying that after he and his mother went to see Tracey in the hospital after the accident and got her prognosis, they went to a visitors’ waiting room where his mother had a series of bitter questions.

“How could God do this to Tracey?” she asked. “How could God do this to us? What more does God want from me in this life? Where the hell is God?”

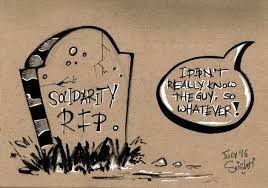

Leonard, an Australian Jesuit priest, made that last question the title of his book, in which he writes that he told his Mom that if anyone could prove that God was the cause of Tracey’s accident, he would leave “the priesthood, the Jesuits and the church.”

“I don’t know that God,” he told his mother. “I don’t want to serve that God, and I don’t want to be that God’s representative in the world.”

The questions Leonard’s Mom asks are undoubtedly among the most common asked by believers and non-believers when tragedy strikes. And the tragedy doesn’t have to involve severe bodily damage as in Tracey’s case. It could be chronic pain over a long period; ongoing depression; a string of bad luck or even perceived bad luck.

The questions are also among the many we ask about a God who is said to be all-powerful and all-knowing and at the same time loving and merciful. They are among the primary reasons for rejection of the God of Christians and Jews, in fact.

I’ve written before about why bad things happen to good people, quoting from the famous book by Rabbi Harold Kushner. I think the subject deserves more attention because it goes to the heart of our ideas about God and his/her relationship with us.

Leonard’s sister told him that since her accident, she had heard “every religious cliché in the book regarding suffering and God’s plan.”

Indeed, we religious people have our self-justifying platitudes, such as the one that insists that HIV/AIDS is punishment for homosexuality, or that God sends hardship and catastrophe to help us grow in faith or that “except for God’s grace, I could have been seriously injured in that accident.”

Failing to take into account the culture of the times and the authors’ goals, many people adopt the literal image of the God of the Hebrew Bible who is swift to punish wrongdoing, or simply punish people he doesn’t like. This God is arbitrary and spiteful. Or they see God as an uncaring observer of human activity, a God who can’t be all-powerful because he/she made an imperfect world.

Accept Things As They Are

Leonard wants us to simply accept things as they are. “Given that God wanted to give us the gift of free will, even to the point where we can reject God … maybe this world is as good as it gets,” he writes.

God does not send evil. He/she doesn’t play us like pieces on a chess board. Leaving aside such questions as the existence of hell, God doesn’t punish us in this world. Jesus’ God, according to Mathew’s gospel, “makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust.”

God is not a controlling and suffocating parent, either, but a loving, caring one. So, how should that affect our search for God? It should assure us of its practicality and that the search will be worth the effort.

“Nothing is more practical than finding God;” writes Leonard, “that is, falling in love in a quite absolute, final way. What you are in love with, what seizes your imagination, will affect everything. It will decide what will get you out of bed in the morning, what you do with your evenings, how you spend your weekends, what you read, who you know, what breaks your heart, and what amazes you with joy and gratitude. Fall in love, stay in love, and it will decide everything.”