Where to Look for God

“If people say they just love the smell of books, I always want to pull them aside and ask, to be clear, do you know how reading works?”

I found this one-liner on the Internet recently. Besides being funny, it illustrates how we often miss the obvious. It also reminded me of a scene in the 1991 movie, Black Robe, a film adaptation of the book of the same name written by Brian Moore.

The story is about French Jesuit priests who, in unbelievably impossible conditions, tried to convert native Canadian tribes, some of whom were considered barbarous even for the 1600s. One of the priests was traveling with a French layman and a small group of tribesman in the Canadian wilderness.

Some of the tribesmen had learned French and the priest began explaining reading and writing, a “technology” with which the natives were completely unfamiliar. To illustrate, the priest wrote something on a tablet, whispered what he wrote to a nearby native, then handed the tablet to the native to show to the other Frenchman.

When the Frenchman read back what the priest had written and had whispered, the native was astonished, and began to tell the others about the “magic” that had just occurred.

Incredible Advancement

Before seeing that scene, the incredible advancement in human communication represented by reading and writing hadn’t occurred to me. Again, missing the obvious.

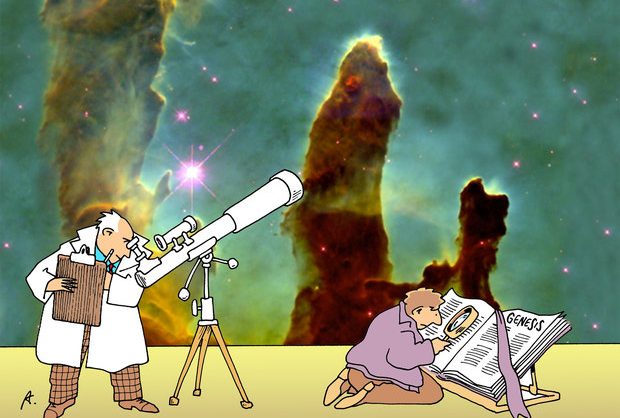

That brings me to my friend and former colleague, Jim Hardy, who wrote: “On an ordinary day, there are 400 billion suns in our Milky Way galaxy alone that burn and explode in cataclysmic fashion, with a ferocity beyond the limits of even a healthy imagination.

“The very effort to get one’s mind around that phenomenon can cause one’s knees to buckle. This is an ordinary day. That is an ordinary fire, albeit in a remote outpost of God’s kingdom.”

He quotes famed theologian and paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin and author Annie Dillard.

“By means of all created things, without exception,” wrote Chardin, “the divine assails us, penetrates us and molds us. We imagine it as distant and inaccessible whereas, we are steeped in its burning layers.”

Writes Dillard: “We live in all we seek. The hidden shows up in too-plain sight. It lives captive on the face of the obvious – the people, events, and things of the day – to which we as sophisticated children have long since become oblivious. What a hideout: Holiness lies spread and borne over the surface of time and stuff like color.”

What’s the point? It’s that, like lingering perfume, God is knowable through his/her effects. The meaning of those effects were obvious to our human ancestors but we have become oblivious to them.

Somewhere in the vague mists of my upbringing, I recall being told that when you pray, you should “place yourself in God’s presence,” and that’s what I try to do daily. Directly, God is unknowable; you can’t get your head around him/her the way you can created things or people.

But if you’re tuned in, you can see his/her effects in everything and everyone, in and around you and the billions of other people everywhere, whether they acknowledge God or not. It becomes a way of seeing the world with God in it, and after a while of seeing things that way, it seems obvious.

As If In Gaseous Form

And you can imagine God’s presence, as if in gaseous form, stretching from here to beyond the ends of the universe.

Critics see the world as imperfect and ask how a “perfect” God could make something so flawed. How and why did he/she choose evolution with all its dead-end mutations as a way of creating? If there is a God, couldn’t he/she just have “zapped” everything into existence?

But don’t you also have to ask why there is anything rather than nothing? And how earth, in the randomness of evolution, could have evolved into something so breathtakingly beautiful? And how it’s possible that a purple martin can find its way from Brazil to its birthplace in my backyard?

Where to look for God? In the obvious.