What Science Can Teach Us About God

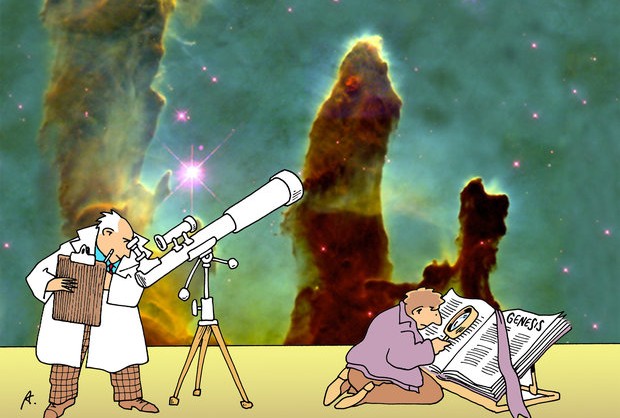

People searching for God gain insights from many sources.

An obvious source, for me, is religion because it directly addresses the question of the existence of God and his/her relationship with humans. And, taking its cue from the nature of humanity, religion pursues God intellectually as well as emotionally.

Science is another valuable source. Adam Frank, an astrophysics professor at the University of Rochester, author and a self-described “evangelist of science,” writes on a recent National Public Radio web site about his insights on awakening one morning during a rain storm. It occurred to him that rain falls in other parts of the universe, as liquid methane on Saturn, sulfuric acid on Venus, for instance.

“We tend to think of ourselves as special, as unique,” he writes. “Our personal stories are so vivid and important to us. Our collective cultural history, expressed in our conflicts this moment, seem so pressing and so urgent. But we really don’t understand what is happening to us at all. We really don’t understand who we are or what we are. That’s why all these rains matter. They help show us.

Part of a Long Experiment?

“In truth, we’re just an expression of one planet at one moment in its many billion-year history. And looking beyond this world, it’s clear we’re part of a long, long experiment in possibilities the universe is running over and over again. All our enormous efforts at war and hatred and separation are simply a failure to understand this simple fact.

Substitute “God” for “the universe” – a concept, not a conscious, thinking being – and you have a beneficial insight.

“We are part of something much larger than ourselves, and our ideas about ourselves,” continues Frank. “And how can we know this is true? We can know because, without doubt, it is raining all over the universe.”

It blows the mind to consider the age and size of the universe, and to recall that we’re tiny specks on an immense background and only a part of something seemingly infinitesimal. It’s also interesting that Frank, who has written extensively about the juncture of science and faith, addresses many of the same questions that religion has asked for thousands of years.

The idea persists, however, that questioning and science are incompatible with faith.

Geneticist Francis Collins, former head of the Human Genome Project and current head of the National Institutes of Health – about whom I’ve written several times in these blogs – went in his 20s from agnosticism to atheism to Christianity. His thought process, reported in an interview cited on an Iowa Public Television web site, is shared by many.

“I read a little bit about what Einstein had said about God, and I concluded that, well, if there was a God, it was probably somebody who was off somewhere else in the universe; certainly not a God that would care about me. And I frankly couldn’t see why I needed to have any God at all.”

In his book, The Language of God, A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief, Collins refers to a book by biologist and theologian Alister McGrath, who makes three important points after citing the “aggressive” atheism of people like Richard Dawkins, an English evolutionary biologist and author.

No Need for God?

First, that because evolution accounts for the origin of life, there is no need for God. That, writes Collins, arbitrarily discounts the idea that God worked out his creative plan by means of evolution.

Second, Dawkins claims that religion is anti-rational. “While rational argument can never conclusively prove the existence of God,” Collins writes, “serious thinkers from Augustine to Aquinas to C.S. Lewis have demonstrated that a belief in God is intensely plausible,” adding that “it is no less plausible today.”

Third, Dawkins, and others, argue that great harm has been done in the name of religion. That’s hard to deny, but those harms “in no way impugn the truth of the faith; they instead impugn the nature of human beings, those rusty containers into which the pure water of that truth has been placed.”

Many people consider themselves agnostic. From the Greek, un or non, and gnostos, or knowledge, agnostics say they don’t know whether there’s a God. Many more are “practical agnostics,” who simply dismiss the question of God because they consider it irrelevant.

But says Collins, “To be well defended, agnosticism should be arrived at only after a full consideration of all of the evidence for and against the existence of God. It is a rare agnostic who has made the effort to do so.”

People searching for God owe it to themselves to make this effort, and to be open to insights from many sources – including science.