The God of Whim, or Dad?

It’s undoubtedly true that the Nazi concentration camps produced many atheists, not only among survivors but among those who know about them.

“Where was God?” many of them and those of us who empathize with them might ask. “How can a good and loving God allow such horror?” We ask that question though it wasn’t God who subjected humans to the gas and torture chambers but “man’s inhumanity to man.”

We may ask similar questions of lesser “horror,” and if it doesn’t result in atheism, it may contribute to a tepidness in our faith or our search for faith. “How can God allow the illness that I’m subject to? What did I do to deserve it? Why don’t things ever go my way? I’m a believer or trying to be. Shouldn’t I get a break?”

Clashes with Theology

Despite the fact that this kind of thinking clashes with theology based upon the Bible or our church’s teachings, many of us cling to the idea that God punishes and rewards us in this life. And it seems to be based on God’s whim. Or, at least, God’s indifference.

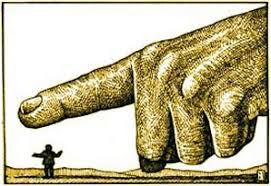

For some reason, many of us can’t shake the image of God as the stern, white-bearded guy who keeps strict tabs on us and our actions. But if this is the God in whom we believe, our faith is a liability, not an asset.

If we’re believers in the Christian tradition, we would be ignoring the God consistently presented by Jesus in the gospels. His God was the father of the prodigal son in Luke’s gospel, a father who patiently waits for the return of a son who asked for his inheritance, went to a “far country” and “squandered it in loose living.”

When the penniless and repentant son returns, the father “yet at a distance … saw him and had compassion and ran and embraced him and kissed him.” Then the father threw a party to celebrate his son’s return.

Not Consistent

Ok, I acknowledge that that image of God is not consistent in the Bible as a whole. The Hebrew Bible, especially, has many references to a God who is jealous, arbitrary and vindictive. But given that among the biblical authors, the image of God evolved over centuries – changing dramatically with the appearance of Jesus – we should try to catch up.

What difference does it make? An image of God as arbitrary and vindictive can’t sustain faith, in my opinion. Who needs a god like that? Such a god proves the point of those who cynically say, “We made God in our image and likeness.”

What can we gain by devotion to such a god? And how can such a faith ever be an asset?

But knowing, if only in a limited way, and loving the God of much of the Hebrew Bible and the major part of the Christian Bible, can be a great asset. That God is a God of love who invites us to love back. And we do that, principally, through loving others.

For me, there’s no greater summary of the benefits of faith than the description of love in Paul’s first Letter to the Christian community in Corinth in present-day, south-central Greece.

Not Arrogant or Rude

“Love is patient and kind; love is not jealous or boastful; it is not arrogant or rude. Love does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable or resentful; it does not rejoice at wrong, but rejoices in the right. Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.”

Ok, you might say, but you don’t have to have faith, or search for it, to adopt this idea of love. No, but faith implies dedication to these ideals and religion provides motivation to implement them, despite the difficulty of adopting these God-like attributes.

And faith implies a relationship with God, which, as the cloud of witnesses attests to over the centuries, is only achieved through prayer – not just asking for things but in cultivation of a friendship with God.

Personally, I like the image of God as father, the image continually presented by Jesus in the gospels. That God is called Abba in Hebrew, which, according to biblical scholars implies an intimate relationship. Some scholars say it’s close to “Daddy” or “Dad.”