Is Wrong the New Right?

Bryce Miller, who formally worked at the newspaper where I was employed, is now a sportswriter for the San Diego Union Tribune.

His very active life was recently interrupted by a diagnosis of cancer and the sometimes-frightful treatments that go with it. He wrote about it in his newspaper, and it was subsequently published in an online newsletter by my former newspaper colleagues. His experiences taught him many lessons.

“I … learned that situations like these provide powerfully emotional doorways to the kindness of others, taken for granted much too often in our stubbornly divided times.

Bombarded with Casseroles

“Life rafts flooded in. My younger brother, Brian, came to San Diego on a one-way flight. Neighborhood friends bombarded me with casseroles. The mailbox bulged with funny T-shirts and handwritten cards. Buoying text messages landed by the dozens, moistening eyes.”

I recently moved from Iowa, which boasts that it’s the home of “Iowa nice.” But my wife, Amparo, and I have noticed that our new state of Colorado is at least as “nice.” We find that the vast majority of clerks, salespeople, service people and neighbors go out of their way to be courteous and kind.

I understand that that’s not everyone’s experience, which reflects where people live, what biases may victimize them, and their own perceptions of reality. But my own experience with others makes it hard for me to be pessimistic about society.

A recent article by David Brooks in The Atlantic magazine had the title, “How America Got Mean.” The subtitle summarizes its gist: “In a culture devoid of moral education, generations are growing up in a morally inarticulate, self-referential world.”

The Context of Kindness and Courtesy

Some people may not think of “morality” in the context of kindness and courtesy, but in my view, selflessness is among the best tests of a person’s knowledge of right and wrong.

Brooks uses a mix of data and interviews to substantiate his view.

“A head nurse at a hospital told me that many on her staff are leaving the profession because patients have become so abusive. At the far extreme of meanness, hate crimes rose in 2020 to their highest level in 12 years. Murder rates have been surging, at least until recently. Same with gun sales. Social trust is plummeting. In 2000, two-thirds of American households gave to charity; in 2018, fewer than half did. The words that define our age reek of menace: conspiracy, polarization, mass shootings, trauma, safe spaces.

“In a healthy society,” he continues, “a web of institutions—families, schools, religious groups, community organizations, and workplaces—helps form people into kind and responsible citizens, the sort of people who show up for one another. We live in a society that’s terrible at moral formation.”

Restrain Selfishness

Brooks writes that moral formation, “as I will use that stuffy-sounding term here, comprises three things. First, helping people learn to restrain their selfishness. …Second, teaching basic social and ethical skills. …And third, helping people find a purpose in life. Morally formative institutions hold up a set of ideals.”

I think Brooks has a point. But one of the problems for society, it seems to me, is deciding whose moral principles to follow. Many people assume that we’re all on the same page in this regard and make ethical and moral decisions by the seat of their pants. “We just know,” they would say.

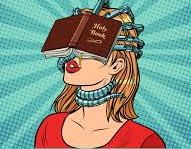

But this is where religion, which is now held in contempt by so many, can play an important role. Many religions have centuries of experience in helping people decide right from wrong. I think dismissing them is a mistake.