How to Die with Dignity

Ron Flug, the husband of my friend and former newspaper colleague, Polly Flug, died several years ago of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease. I’m somewhat familiar with it because my sister-in-law and the husband of another newspaper colleague also died of ALS.

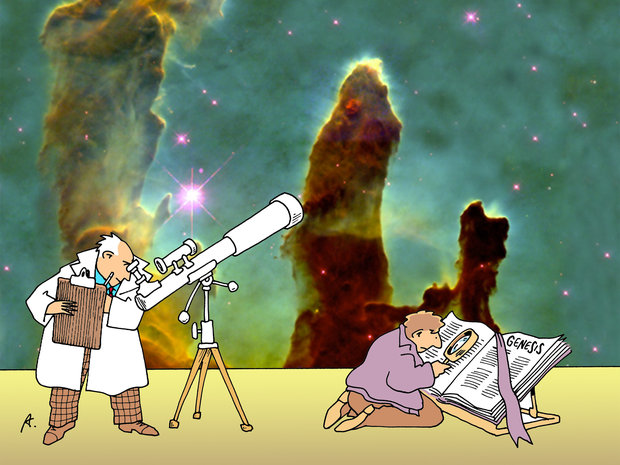

Simply put, the disease is a fatal communication problem – between the brain and the rest of the body. Eventually, patients lose their speech, ability to swallow, to move and breathe, and often die within two years of diagnosis. The disease is sadistic, prompting anyone searching for God to question why God – portrayed in the gospels as a loving parent – could allow it.

I’ve written several blogs on why God allows bad things to happen to good people. The blogs have not definitively or even satisfactorily dealt with the question, of course, but I believe there are rational answers to the question nonetheless. I’ll return to the subject in a future blog. Today I want to write about “dying with dignity.”

That’s the term often used by people who promote assisted suicide, which, with the addition of California as the sixth state to legalize it, is a major issue in the cultural wars. Assisted suicide, its promoters say, allows people to die with dignity.

Skeptical About Assisted Suicide

I’m not writing here as a soldier in the culture wars, and I don’t judge those who choose to die in this way, but I’m skeptical about assisted suicide’s benefits for individuals and society. I’m particularly concerned that we may believe that the dying who don’t choose suicide are somehow not dying with dignity.

Ron Flug’s disease moved much faster than the norm. He was diagnosed in March, 2011, and by July he was pretty much confined to a recliner at home. He was soon living in a hospice, where he died surrounded by family. He benefited by family members’ presence and love; they benefited by being able to help him through it, showing their love and gaining insight into death, and life.

“The night before he died,” Polly told me recently, “there were many family members around in his room.” One by one, they said their goodbyes until only Polly was left, and she got into bed with her husband.

“My thought was, ‘I slept with Ron on the first night of this marriage, and I want to sleep with him on the last night.’” I talked, sang, prayed and just rested with Ron all night. …When he took his final breath at 3 a.m., he got a smile on his face. People will doubt that, but I saw it. And this was a man who had lost all muscle control, even in his face.”

Polly believes he was seeing heaven and Jesus. And, she added, “as sick as he was, there was dignity.”

Dignity, according to the dictionary, is “the quality or state of being worthy, honored or esteemed,” and that doesn’t depend on how much pain you’re in, how much you drool or lose control of your bowels. The Judeo-Christian tradition sees all of us as children of God who have dignity intrinsically, in living and in dying.

That includes people like Ron, a man of faith, and people who see themselves as estranged from God and religion. It includes people who die in accidents, by suicide, of dementia and in war.

We Americans have an irrational and unbalanced attitude about death and suffering. On the one hand, death fascinates us. Few hit TV shows or movies lack scenes, often bloody, in which people die tragically, heroically or as criminals who “get what they deserve.”

On the other hand, writes Jessica Keating in a recent America Magazine article, “we fear death and push it to the margins of lived experience.” And “…we remain keenly aware of death’s nearness, fearful of its capricious cruelty.”

As for suffering, “we are as ill-equipped to encounter suffering as we are to face death.”

But suffering does not devalue human life. Ascribing dignity to a death by assisted suicide “masks the reality of fear and equates dignity exclusively with radical autonomy, choice and cognitive capability,” she writes. “The result is the not-so-subtle implication that the person who chooses to endure diminishment and suffering dies a less dignified death.”

So how can a skeptic who is searching for God view death and suffering with anything less than terror?

A Slow Discovery of Mortality

In his book, Show Me the Way, Henri Nouwen suggests that our lives be “a slow discovery of the mortality of all that is created so that we can appreciate its beauty without clinging to it as if it were a lasting possession.

“Our lives can indeed be seen as a process of becoming familiar with death, as a school in the art of dying … all these times have passed by like friendly visitors, leaving you with dear memories but also with the sad recognition of the shortness of life.

“In every arrival, there is a leave-taking; in every reunion there is a separation; in each one’s growing up there is a growing old; in every smile there is a tear; and in every success there is a loss. All living is dying and all celebration is mortification too.”

“A good death,” Nouwen writes elsewhere, “is a death in solidarity with others. To prepare ourselves for a good death, we must develop or deepen this sense of solidarity.”