Faith through Walking

A few years ago, New York Times best-selling author, Timothy Egan, set out on a journey to find his faith. He detailed his journey in a book published in 2019 called, “A Pilgrimage to Eternity, From Canterbury to Rome in Search of a Faith.”

Egan was a Catholic in the sense that Olive Garden is an Italian restaurant. In other words, he “practiced” his faith occasionally at best. But, late into middle age, he decided he wanted to clarify his beliefs and clear up his doubts. His method: Walk from England to Italy along an ancient pilgrim’s route called the Via Francigena.

Similar to the more famous El Camino de Santiago – the popular, 475-mile trek across northern Spain to the city of Santiago de Compostela – the Francigena is about 1,243 miles. Roughly 1,200 pilgrims a year walk the Francigena compared to an estimated 200,000 who walk the El Camino.

Finding a Spark

A history buff, Egan wanted to walk where countless pilgrims walked in the Middle Ages. He visited shrines and sanctuaries filled with statues and relics of earlier Christian times in hopes of finding the spark that would ignite a faith that was no more than smoldering embers.

Egan faithfully went through the paces of physical preparation by “walking hills and stairs, by breaking in shoes and building calf muscles, by shedding weight and inconvenient thoughts.

“Getting in spiritual shape was much harder,” he writes. “You tidied up your affairs, made a donation to charity. Atoned. You ended a 30-year feud with a man you’ve known since college. Although, when you told him all was forgiven, he responded with a quizzical look and said, ‘Were we in a feud?’ You hope the soul has not gone dark. You’ve given it a scrub, cleaned out the grime from long-held grievances, petty jealousies, and a spell of intolerance. The goal is to be fresh, open to possibility.”

He was alternately inspired and disgusted by the churches, monasteries, shrines and relics he encountered. And by the end of the book, I can identify two areas of faith that he cleared up.

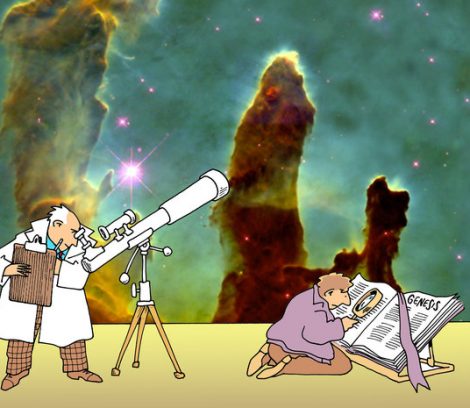

The first was a basic belief in God. Egan found still to be relevant one of the “proofs of God” of the medieval theologian and philosopher Thomas Aquinas – the idea that creation needs a first mover.

Origin of the Universe

Egan noted that famous cosmologist and atheist Stephen Hawking, who died in 2018, said, “The one remaining area that religion can now lay a claim to is the origin of the universe.” That’s because science has so far been unable to determine what triggered “the big bang” or the origin of what fueled it, or substantiate any other possibility of how the universe began.

And Egan seems to agree with a remark by Napoleon, the enigmatic emperor of France, that “without religion, one walks continuously in darkness.”

The other area was more surprising, in my view.

“I believe in the Resurrection, and I owe this sentiment to the Via Francigena,” he writes toward the end of the book. I find this surprising because it is one of the most difficult articles of belief for Christians and non-Christians alike. That Jesus rose from the dead challenges everything we know about how life works, but as St. Paul points out, it is essential to belief in Christianity.

Compelling Argument

“The evidence from the first century, the many people who swore they had seen the risen Christ and chose death rather than recanting, is a compelling argument – for who would die for a fraud.” Egan notes that St. Augustine taught that miracles aren’t contrary to nature, but only “what we know about nature.”

Egan’s trek across Europe, his way of connecting to a faith tightly embraced by his loving mother but loosely held by Egan, is a lesson for people who continually put off deciding the most important questions of human existence. So many people seem to put everything else before their search for God.

Egan’s quest cost lots of money, lots of sore muscles, lots of nearly ruined feet and ankles, but because he was able to clarify at least two pestering issues about God, it was well worth it.