Do We Really Need a God like Us?

When I worked as a priest in Bolivia, I was told that the Aymara-speaking people in my parish would do anything short of murder and mayhem to get their babies baptized, and that turned out to be partially true. They used all manner of tricks to get you to baptize their children without them having to go through any kind of education on the meaning of baptism.

Reportedly, the community-imposed penalty for ignoring their deeply felt obligation to baptize children – perhaps imposed by early Spanish missionaries – was exclusion from the community. That may not seem like a big deal, but to the people of the Altiplano – the high, arid plains of Bolivia – the community was everything. It was crucial to their income, their mental and physical health, and their continued relationships with family. It entirely comprised their socialization.

So when a disaster – such as a hailstorm that wiped out the crops – struck, the elders would search the community looking for babies that had not been baptized. Because Altiplano hailstorms were so selective, devastating the crops of some residents while ignoring the crops of neighbors, it was obvious to them that disasters were punishment from God for, among other reasons, ignoring the requirement of baptism.

Childish Ideas of God Pervasive?

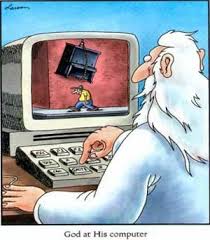

We in the U.S. may feel ourselves much too sophisticated for such views. But are we really? The view that so many of us have of God shows that superstitious and childish ideas about God are pervasive. And many people who reject God and religion are rejecting those false notions of both.

The idea of a vengeful God, as if he/she were like us, is probably the most common, even though the Hebrew Bible says that humans were made in God’s image, not vice versa. It’s true that the Hebrew Bible sometimes portrayed God as vengeful, but that occurred in the early stages of the evolution of the relation between God and humans.

Anyway, according to Tomas Halik, the philosopher and theologian I often quote in this blog, even atheists secretly hold such views of God – perhaps explaining in part why they reject the God they secretly fear.

“There is a Czech play in which the protagonist declares that he is such a convinced atheist that he is often afraid that God will punish him for it,” writes Halik.

Like Customers with a Car Salesman

We often hear or read things like, “I had that accident because I haven’t done what I could for my elderly mother.” Or, “that guy contracted AIDS because God doesn’t approve of homosexuality.” Many of us also bargain with God, like customers with a car salesman. “Get me that new job and I’ll go to church,” as if going to church benefits God.

“…There are many people who have long maintained a childish notion of a magic god,” writes Halik, “a god of banal consolations and superficial optimism, a ‘guardian angel’ at our service, an inveterate comforter who tells us everything will turn out alright, a household god intended to fulfill just one single role: ‘working’ as an infallible granter of our most fatuous wishes.

“Cozy little gods like that logically collapse when faced with the first serious crisis of our lives,” he continues. “After taking leave of a god of that variety, quite a lot of people – often with a certain pride in discovering the truth about the ‘real world’ at last – declare themselves to be ‘atheists.’”

So, how are we supposed to “know” God as he/she really is? We can’t, of course. We have the Christian and Hebrew bibles, but we still see “only through a glass darkly,” knowing God only by analogy. That’s what it means to “walk by faith, not by light.”

The exception to this inability to know God, of course, is the belief of Christians that Jesus is God in human form. As wild an idea as that seems, an estimated 2.2 billion people ascribe to it. Personally, once I get past the idea of God’s existence – the idea of a superior being who is the author of creation and who knows us and loves us – it doesn’t seem so unlikely.

That’s what the word “incarnation” means, of course, that God took on the flesh of humans. The other important part of this for Christians is that it didn’t just happen some 2,000 years ago. Jesus and St. Paul – who may be more responsible than any other follower of Jesus in forming Christianity – taught that Jesus continues to be present in us and in others.

Not Just “Charity”

That’s why, for Christians, loving our neighbor isn’t just a matter of charity. It’s what it means to be a Christian. Some people want to disown others who fail to attend church, who ignore God and religion or act in a way they disapprove, but all of these failures pale in comparison to the failure to love.

Love – as distorted and trite as the word has become – was the hallmark of Jesus’ teaching, and loving others is the way we continue to love Jesus. It is also the best way to help others find God, and make a genuine contribution to the world.

“Wherever we follow in His footsteps by bringing others closer to us,” writes Halik, “including those ‘at a distance,’ the rule of God on earth is widened.”