Do Right and Wrong Actually Exist?

Recently, Cyrus Vance, the district attorney for Manhattan, brought felony charges of rape and criminal sexual acts against Harvey Weinstein, the famous film producer.

The case has produced a ton of publicity, partly because Weinstein has been denounced by several high-profile movie stars, and has been roundly criticized by people in and out of the movie industry. The case has been major fuel for the #metoo movement.

I would guess that Weinstein, who has pleaded not guilty, is unusual in drawing criticism from the left and right, from Democrats, Republicans and Independents, and everybody in between. We all think his actions, if proven, are despicable, another case of the crass abuse of power.

But perhaps few of us have thought about why his alleged actions are contemptible. “They just are,” we might say. And that brings us to the subject of how to tell right from wrong, which itself may provoke the response from some readers that “We just know.”

Simply a Matter of Opinion?

I wrote a blog about this topic a few years ago, promising to return to the subject, and I think it’s time to write about it again because apart from those who think the answer to questions of right and wrong are easy, there are evidently more people than ever who think that right and wrong is simply a matter of opinion.

Their view is described as “moral relativism,” the notion that there are no objective moral standards.

We make routine right-and-wrong decisions every day, choices such as whether to return money we’re overpaid in a checkout line, whether to let someone know when we’ve dinged their car, whether to help a friend, and these decisions may be relatively easy and seem intuitive.

And I believe most people – young or old, aware of it or not – are guided by the objective moral standards they learned at home and/or by the faith they may no longer profess. We may not give them much thought, but the principles that guide us are based on objective standards inculcated in most of us from the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Objective Standards?

The bigger moral and ethical questions, of course, are more challenging and it’s generally those that evoke the controversy about objective standards of right and wrong. They’re issues like abortion, assisted suicide, same-sex marriage, the death penalty, the use of military drones, etc. The solutions to these problems are not obvious, at least they shouldn’t be. With good reason, rational and moral people have differing views on these subjects.

Does that mean that these disagreeing people are not guided by objective standards? Not necessarily because we can disagree about how the standards are applied or which standards are applicable. The important thing is to agree that there are standards.

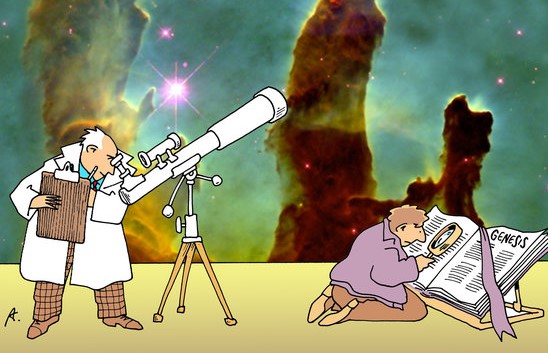

Looking at the question from the point of view of a religious tradition makes it easier to answer moral questions, of course. Moral standards are embedded in the traditions of Christians, Jews and Muslims and many other religions, even though followers of these religions often fail to follow them.

But apart from religion, it is obvious to many of us that there are standards, though not always explicit or exact, that are discernable by all reasonable people. Indeed, most people share a view of what’s right and wrong. Most people, for instance, believe that lying, cheating, stealing and hurting others is wrong, even though they may not be able to explain why. Many of us believe that’s because an elementary moral code “is written on our hearts.”

“Self-Evident”

Indeed, the writers of the Declaration of Independence held this view, declaring that certain truths are “self-evident,” and aren’t subject to the whims of government leaders or anyone else. And it was the basis of the famous Nuremburg trials that condemned Nazi leaders who rejected their consciences, claiming they were merely following the law or orders in murdering millions of Jews and others.

The idea of such a “natural law” is an ancient one, expressed by the Greek philosophers who, according to Wikipedia, asserted “that certain rights are inherent by virtue of human nature, endowed by nature – traditionally by God or a transcendent source – and that these can be understood universally through human reason.”

If as a society we abandon the idea of objective moral standards, we’re in big trouble. There would be no basis for condemning lying, cheating, stealing or hurting others or criticism of people like Harvey Weinstein. We may disagree on how to apply them, but we must agree that right and wrong do, indeed, exist.