A Guide to Finding Faith?

Some years ago, a friend of New York Times opinion columnist Ross Douthat told Douthat that, “If appreciating some of the ideas in St. Augustine’s ‘Confessions’ was enough to make you a Christian, then I’d be a Christian. But a personal God? The miracles? I can’t get there yet.”

That’s how Douthat begins his recent, lengthy article in the Times, titled “A Guide to Finding Faith.” Its subtitle: “In the modern era, there are reasons to find the idea of God more plausible than ever.”

Douthat, 42, is described by Wikipedia as “an American conservative political analyst, blogger, author and New York Times columnist. He was a senior editor of The Atlantic.

In “A Guide to Finding Faith,” Douthat says that much of his mail about his views is some version of the sentiment expressed by his friend. Sometimes, he writes, “it’s couched in the form of regretful unbelief: ‘I’d happily go back to church, except for one small detail — we all know there is no God.’”

Many Would Like To Believe

Like them, he writes, many people would like to believe and would even like to find the motivation to return to church. They would like to pass on their religious heritage to their children. They find some religious beliefs and practices intriguing, even inspiring. But they can’t make the leap of faith, and the struggle simply leads back to unbelief.

Douthat suggests starting by “questioning the assumption that it’s really so difficult, so impossible, to credit ideas of God and accounts of supernatural happenings.” And he asks, “What if atheism is actually the prejudice held against the evidence?”

The materialist biases of secular culture, he writes, are “like a spell that’s been cast over modern minds, and the fastest way to become religious is to break it.” Here’s how he defends this view.

It made sense, you may think, for an intelligent person in ancient, medieval and pre-Darwin times to believe in God. Douthat asks his readers to put themselves in the place of a pre-Darwin person for whom God seemed to answer questions about the world that couldn’t otherwise be answered.

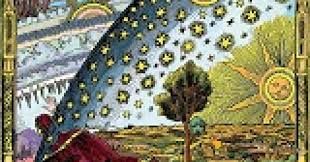

Vivid and Beautiful and Awesome

He or she believed the universe was created “with intent, intelligence and even love,” he writes. The world was “not just orderly, law-bound and filled with complex systems necessary for human life, but also vivid and beautiful and awesome in a way that resembles and yet exceeds the human capacity for art.”

The idea that human beings are fashioned, in some way, in the image of the universe’s creator made sense. Unlike the other animals, you had an almost God-like view, “constantly analyzing, tinkering, appreciating, passing moral judgment.”

Finally, the religious view that humans are connected to a supernatural plane explained why your world contained an incredible variety of experiences described as “mystical” or “numinous,” unsettling or terrifying, or just weird.

Aren’t all those observations still valid, he asks, despite the discoveries of modern science?

Strange Fittedness

But it’s not only a matter of “despite” those discoveries because science “and the experience of modernity have strengthened the reasons to entertain the idea of God.” Among those reasons is “the strange fittedness of our universe to human life,” through “the mathematical beauty of physical laws” and “their seeming calibration for the emergence of life,” which are much clearer to us than they were to people 500 years ago.

Fact is, as fascinating and useful as science is, it leaves unanswered lots of important questions, such as why is there something rather than nothing and why the earth, despite its dangers and natural catastrophes, is so attuned to human life. Another is why nature leaves so many human beings still yearning for something deeper, for meaning, even for a spiritual life.

None of these points “proves” the existence of God nor may they convince you of the value of religion, but they should make you consider both.