How Could God Allow Dallas, Baton Rouge, St. Paul?

I once had a heated conversation with a police officer on the subject of evil, specifically, whether some people are simply evil, as he contended, or whether as I maintained, people “go bad” because of life circumstances or factors we don’t yet understand.

Several weeks later, the officer’s wife was jogging on a trail in Minnesota when she was brutally attacked by a man who did all he could to kill her. He strangled her, beat her and used a stick to gouge her eye. She fought him and survived but she lost the eye and was badly injured.

As I recall, the attacker was taken into custody, and presumably prosecuted, but no cogent motive was ever provided. When I read about it in the newspaper, I recalled the conversation with the officer and reconsidered my theory about evil.

An Agnostic on the Subject

I didn’t come around to the officer’s view but became an agnostic on the subject, having to acknowledge that I just don’t know. I want to believe that humans are basically good. I’m also uncomfortable with labeling people as “evil” because it justifies the use of violence to destroy the evil.

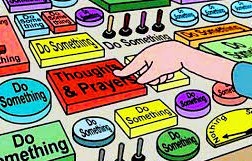

The “problem of evil” has always been one of the principal stumbling blocks for people who want to believe in God. Since the beginning of Judeo-Christianity, people have asked how a good God could allow awful things to happen. Undoubtedly after the recent shootings involving the police in Dallas, Baton Rouge and St. Paul and the terrorist attacks in Orlando, Istanbul and Baghdad that left 300 people dead, many people are asking that question.

My preferred argument is to consider the alternative to God allowing evil: a determinism that doesn’t align with the image of God as parent. How could we have the freedom to reject God if he/she prohibited bad people and evil acts?

This problem was much on the mind of Elie Wiesel, the author and Nobel Peace Prize winner who died recently at age 87. A prolific writer and peace advocate, he had good reason to focus on the problem of evil having survived one of the most cruel, inhumane and horrific systems imaginable, the Nazi concentration camps.

An online paper by Robert E. Douglas Jr. on Ellie Wiesel’s Jewish faith quotes from Wiesel’s novel about Auschwitz, The Gates of the Forest:

“The executioner killed for nothing, the victim died for nothing. No God ordered the one to prepare the stake, nor the other to mount it. During the middle ages, the Jews, when they chose death, were convinced that by their sacrifice they were glorifying and sanctifying God’s name. At Auschwitz, the sacrifices were without point, without faith, without divine inspiration. If the suffering of one human being has any meaning, that of six million has none.”

One can only imagine what effect such suffering, and witnessing such horrors, would have on one’s faith. Wiesel spent his life helping us to imagine it, we who have much less reason to question God’s part in the evil we see around us.

To say that Wiesel had a problem with a God who allows massive evil is an understatement. But that doesn’t mean he gave up on God or his faith. He cleared that up in a 2006 interview with Krista Tippet on American Public Media radio.

Divorced God?

“Some people who read my first book, Night, they were convinced that I broke with the faith and broke with God. Not at all. I never divorced God. It is because I believed in God that I was angry at God, and still am. But my faith is tested, wounded, but it’s here.

“So whatever I say, it’s always from inside faith, even when I speak the way occasionally I do about the problems I had, questions I had. Within my traditions, you know, it is permitted to question God, even to take Him to task.

“I never doubted God’s existence. I have problems with God’s apparent absence, you know, the old questions of theology. And they are topical even today.”

What sustained him, and should sustain us who are searching for God?

“I went on praying,” he told Tippet. “So I have said these terrible words, and I stand by every word I said. But afterwards, I went on praying.”